Divesting, Buffett’s most powerful capital allocation skill

Download the checklist

You’re a business owner.

You’ve spent an enormous amount of energy and money on existing business lines.

But some of them are not performing. Just as in investing when you have a position you’ve researched for hours, it is down, and you’ve might have found another opportuinity, there’s some significant commitment bias and loss aversion going on in the decision-making process.

The right thing for the manager to do would be to take the loss, maybe sell the assets, and use the freed-up cash to strengthen an existing, profitable business line.

Most CEOs want to make their company BIG. A unicorn. A Billion dollar company.

Buffett thinks a bit differently.

Of course, he built a Billion dollar conglomerate, but when looking at the actual decisions he made, he sometimes took revenue cuts, to focus on profitability. His focus is on the ‘good’ kind of growth, the one where your return on invested capital exceeds the cost of capital. This means taking short-term pains because you know it will pay off in the longer term.

Remember our article on capital allocation. ⬇️

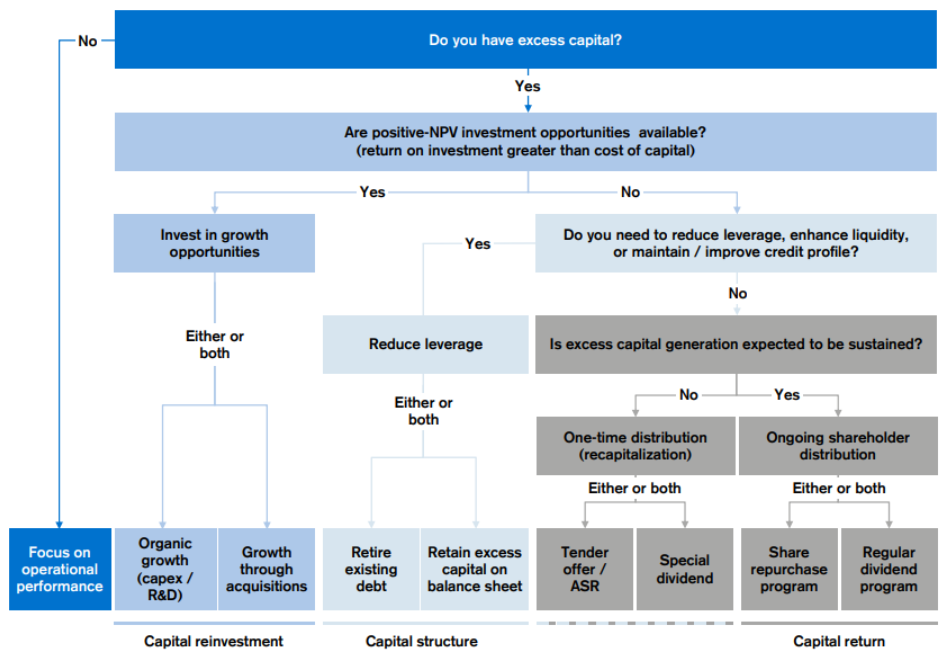

We used this chart from Credit Suisse:

But it already starts with excess capital. It doesn’t talk about where this capital comes from. In that article, I simplified things:

But I swiftly breezed over the asset sales part. And secondly, this diagram does not depict what NOT to do. It only shows what you could do at any given moment.

Let’s go back in time, and get a glimpse on why Buffett is a master capital allocator. Our goal is to see if we can improve our capital allocation checklist.

Berkshire from 1955 to 1985

Jacob McDonough did some investigating work. He spent time in the library, uncovering financial statements and Moody’s pages from the past. His goal was to understand what Buffett did before and during the time he bought Berkshire.

What did Buffett ‘see’?

What did the financial statements look like at that time?

You can find all the details in a great book he has written: Capital Allocation: The Financials of a New England Textile Mill.

I like the following starting description of the book:

Capital Allocation is the true story of a once-dying company who rejected its fate and carved out a unique path to success.

Here’s a short summary of some of the things that happened during that time. (we covered parts of this in The Deals of Warren Buffett).

Buffett considers buying Berkshire his biggest mistake.

When he first bought shares, it was a cigar butt investment, he bought far below book value. He then continued to acquire more shares (because of ego, at a certain moment, somebody wanted to buy his shares, but he changed pricing at the last moment. Buffett did not like that way of doing business).

Once he owned it, the business itself sat in a dying industry. But then this happened:

Buffett attributes these two good years to “luck”, and perhaps the improvement in operating conditions was luck, but Buffett’s skill with respect to redeploying the cash flow was not luck.3 Most managers of a textile company would have taken that cash and reinvested it into the business, probably buying new equipment that, at best, would provide only a fleeting competitive advantage. The long-term future of textiles was still dim, regardless of a couple of years of profits. Buffett recognized this and began to allocate capital away from textiles.

From The Rational Walk

This is the neglected skill of capital allocation. The fact of NOT pouring additional cash into a losing business proposition. Doing cost cutting and increasing the cash by doing some asset sales and reinvesting them.

These are the skills you see less often.

I’m not going into the whole story, but after buying his first insurance business, and creating a holding company where more and more cash is generated which he was able to deploy in more and more accretive business, well we know how that played out.

The beauty of a conglomerate

Say you have a business, like a tollway business as we previously discussed. Growth might be limited, but the company is churning out cash every year. The only thing the toll bridge business can do for its shareholders is to pay out a big portion in dividends. This is what the tollway companies do.

Now a holding company comes in and buys the business. Instead of paying out dividends, it uses the cash to reinvest in other businesses. This avoids tax losses on the dividends and offers the opportunity for a better ROI on your investments. If executed well, these kinds of companies can compound returns over a long period of time.

The playbook then becomes:

Buy cash-rich businesses at a reasonable price, and reinvest the cash back into the business or in something better

Buy a business with a good and a bad business line. Close down the bad ones so that the overall business is profitable. Repeat 1.

This of course means that you need to get your hands on the cash, so you need to be able to acquire the company. There are several holding companies or serial acquires that have successfully employed this playbook. Think Constellation Software.

If you want to learn more about family-owned holding companies the Valuing Dutchman is an expert on the topic.

If you want to dive deeper into some of these serial acquires, then The Compounding Tortoise is your place to go.

Do you own a holding company or a serial acquirer? If so, which one?

Invert

Now that we’ve reached a newfound appreciation of asset sales or cutting investments in a bad business, let’s go back to the capital allocation chart, and like Charlie Munger would have said, invert.

Imagine an owner managing a business, what must he or she, from a capital allocation viewpoint, do to drive it into the ground?

Reinvest cash in a business line where ROIC < WACC. We just need more time. We just need one more contract, only one!

Make expensive acquisitions to find synergy (the magic word) and destroy value in the process

Do nothing, just leave the cash pile on the balance sheet. Keep piling it up, you never know what might happen in the future. (several net-nets in Japan)

Only growth matters, even if debt increases. Let’s take on huge risks to build that billion-dollar company (Carvana?)

Buy back shares disregarding the value of the company. Just buy back each year no matter the price in the market

Continue increasing the dividend, even if business prospects are worsening. After all, we’re not going to cut it right? We’ll get massacred by our shareholders

Summary

The above analysis allows us to improve our capital allocation checklist.

Is there proof of the company divesting or cutting business lines in the past?

If they buy back shares, are they considering the intrinsic value of the company?

In the past, when the business suffered, did they have the courage to cut dividends?

I generally prefer buybacks to dividends:

Because it is more tax-efficient

Because the market won’t fling when buybacks stop, as opposed to dividend cuts

I’ve added these questions to the capital allocation checklist, and made a second version of it:

You can download it for free below, or check out the Tools section on the site.

If you think there are still some important questions missing in this checklist, please let me know through the comments or DM me.

Further reading on capital allocation

I’ve added some additional articles on capital allocation below. The more I study business and annual reports, the more I think management with great capital allocation skills is pretty rare. So when you find it, and the business looks undervalued, don’t hesitate.

As Druckenmiller would say

Go for the jugular

Here are 3 great resources to go even deeper into this topic:

A great interview with Jacob McDonough on his book

A YouTube video with Andrew Kuhn and Geoff Gannon on Mastering the Art of Capital Allocation

The Focused Compounding website has an entire section dedicated to Capital Allocation.

In the coming weeks, I’ll write about a company whose assets were sold to divest an unprofitable business line and reinvest everything into a profitable one.

May the markets be with you, always!

Kevin

Good transition to sell INMD and focus on Serial Acquirer

Subject very well covered Kevin. Well done. Capital allocation is the average investors "blind spot'.