5 takeaways from Lynch’s 29% CAGR to find multibaggers

Life Cycle Investing

Some investors focus on one specific style. I have friends who focus on special situations, while others make their money through growth investing.

All roads lead to Rome.

I like to invest in the entire life cycle of companies. I do not know if Peter Lynch thought about it consciously, but that’s more or less what he did.

He didn’t limit himself to a strategy. He had no dogma.

He just wanted to make money.

Hallelujah.

He owned:

Cyclical manufacturers

Fast-growing franchises

Thrift conversions (Jimmy Stewart Banks) -> 5x in 5 years

…

I’m invested in startups, growth companies, mature companies, net-nets, and even one that was in decline.

One thing is certain.

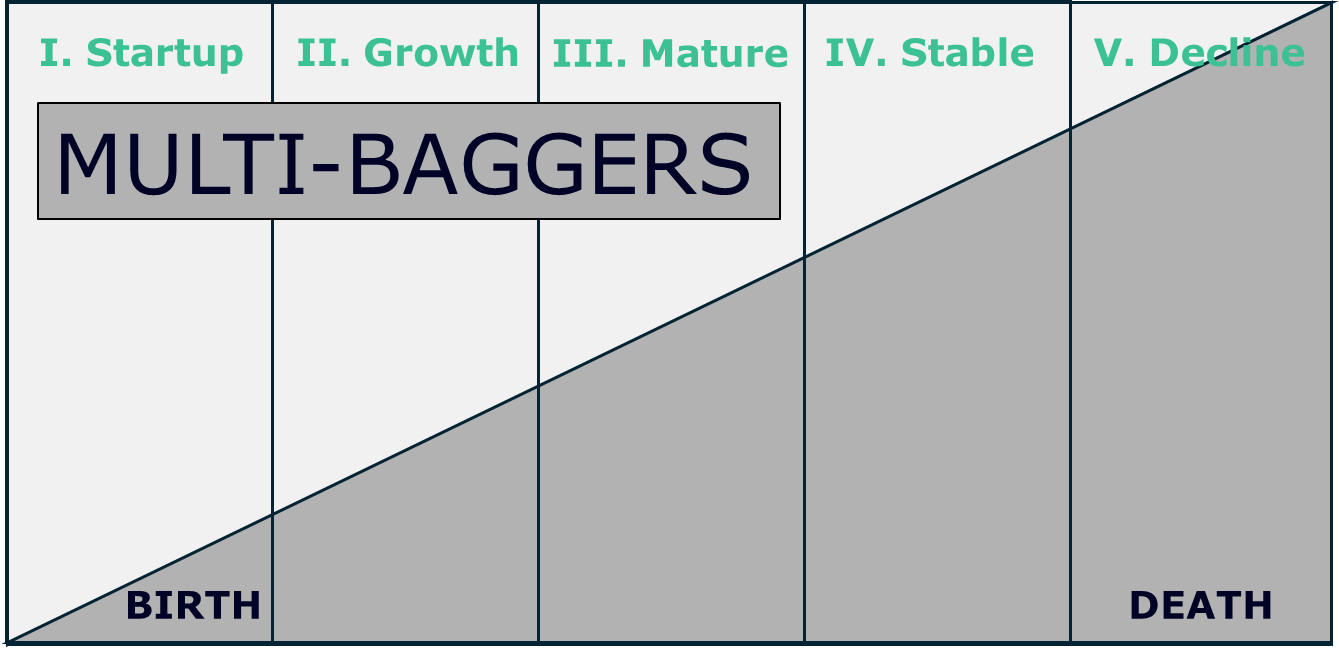

You want to find multibaggers, you need to be early, and you need lots of growth.

Today, we’ll go through the different stages of a company lifecycle, what’s specific about each stage, and how you handle companies in each one of them.

What is a lifecycle?

Damodaran defines 6 stages. Mauboussin has defined 5. The number is not that important. For this analysis, I decided to go with Damodaran, but fused the first 2 stages into 1: One single startup stage.

Based on our data analysis, 100-baggers reside in the first 3 stages. A long runway for growth matters.

Let’s go through them.

Stage 1: Startup

In the startup stage, a company moves from a mere idea to creating its initial products or services and begins to seek its first customers. This phase is defined by extreme uncertainty about both the product’s viability and the effectiveness of the business model, leading to negative cash flows as costs far outstrip any early or non-existent revenues. Founders must navigate the balance between maintaining control and bringing in external expertise and capital to stay afloat, all while burning through funding and striving to establish a repeatable model and product-market fit.

This stage has grown longer over the last 20 years. Amazon IPO’d at a 500M USD market cap. But the venture capital market has matured, and more and more companies have to become unicorns (1B USD) first. This also means that some companies leave the startup fast and go into high growth without ever going public (think Stripe, for example).

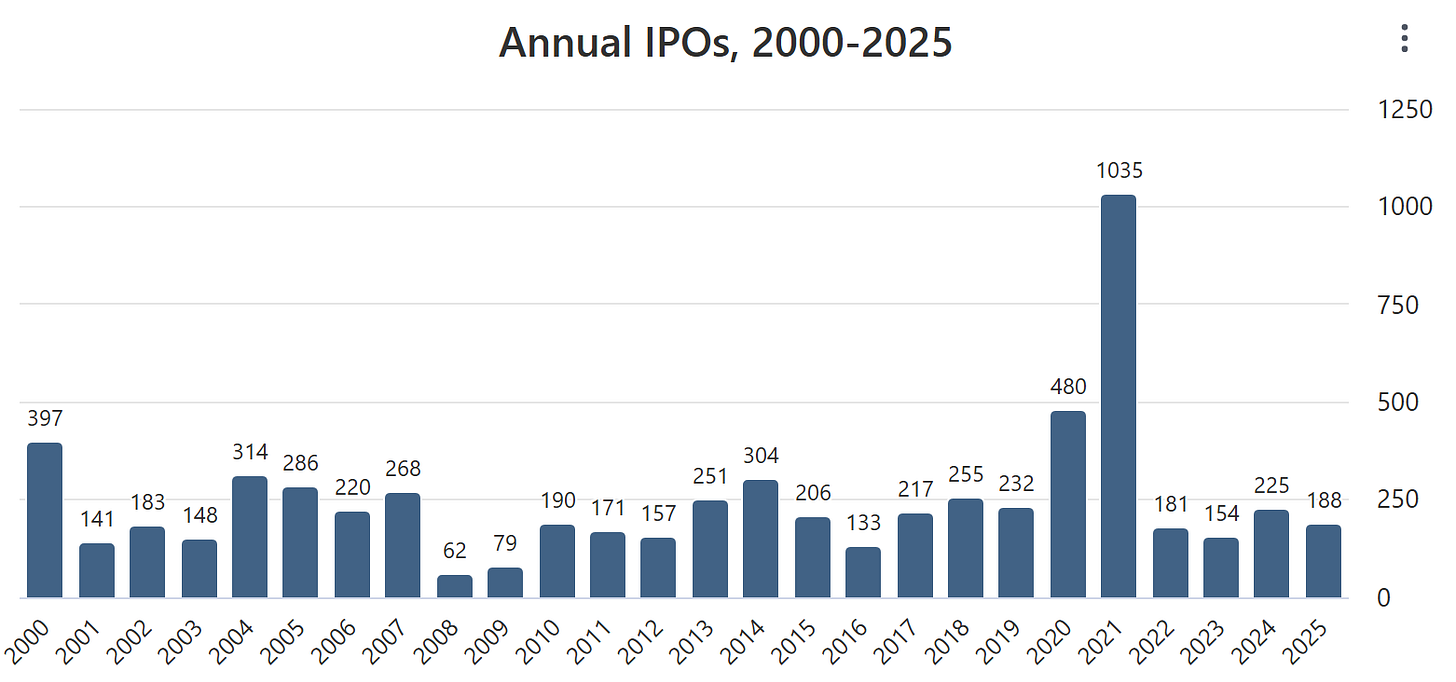

Although the IPO market is far from dead. Here’s the data for the US:

Example of companies:

Cradlewise (Smart bassinets with integrated AI-powered baby monitors) -> it’s like a theme park ride for babies 😁

Adalo (Drag and drop no-code app builder) -> anyone try this one?

Deepgram (AI/Voice Tech) -> Maybe you’ll recognize their voice when talking to customer support?

Stage 2: (High) Growth

The high-growth stage is characterized by a rapid increase in revenues as the company starts to gain significant traction, though expenses often escalate in tandem due to the ongoing need for investment in scaling operations, acquiring customers, and expanding into new markets. At this point, the challenge shifts from simply surviving to proving that the business can scale efficiently without introducing major operational breakdowns, while larger infusions of outside capital are often required to support aggressive expansion and fend off emerging competition.

Example of companies: Lemonade (LMND), OpenAI, Scale AI (49% stake by Meta now)

Stage 3: Mature (Growth)

During the mature growth stage, the company continues to grow, although at a decelerating pace, with profitability improving as economies of scale are more fully realized and cash flows may become consistently positive (operational leverage). The organizational focus moves from rapid expansion to sustaining competitive advantages, streamlining operations, and solidifying the brand, as the leadership prepares for a period of more measured, sustainable growth, and the risk profile gradually changes.

Example of companies: Meta (META), Apple (AAPL), Netflix (NFLX)

Stage 4: Stable (Growth)

In the mature stable stage, the company has largely reached its potential within its core markets, with growth rates settling down to match the broader economic environment and profits stabilizing at high, predictable levels. Strong cash flows allow the company to shift capital allocation from expansion to maintaining operations, often leading to increased dividends or share buybacks, though there is a risk of complacency as innovation slows and bureaucratic practices begin to take root.

Example of companies: Procter & Gamble (PG), Johnson and Johnson (JNJ), Coca-Cola (KO)

Stage 5: Decline

The decline stage sets in when market dynamics or disruptive innovations cause revenues and profits to shrink, prompting the company to cut costs, restructure, or downsize in response to diminished demand. Management faces tough endgame decisions about whether to liquidate, sell assets, or try to reinvent the business; the overarching challenge is to preserve as much remaining value for shareholders as possible or, if feasible, find a new direction to restart the growth cycle.

Example of companies: UnitedHealth Group (UNH), Paramount Global (PARA), WeWork (WWOK)

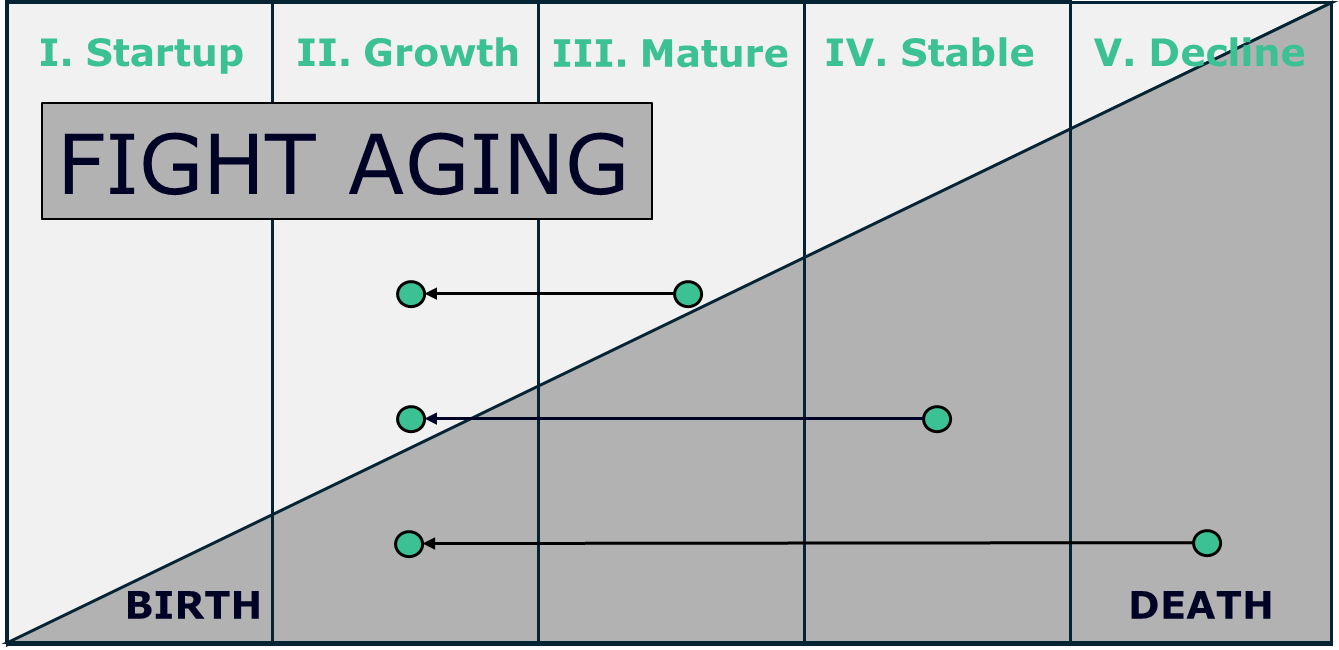

Fight ageing

What’s important is that a company does not linearly go through every stage. The best companies reinvent themselves, build new products, and beat the aging effect. This means they revert from the mature or decline stage back into the growth stage.

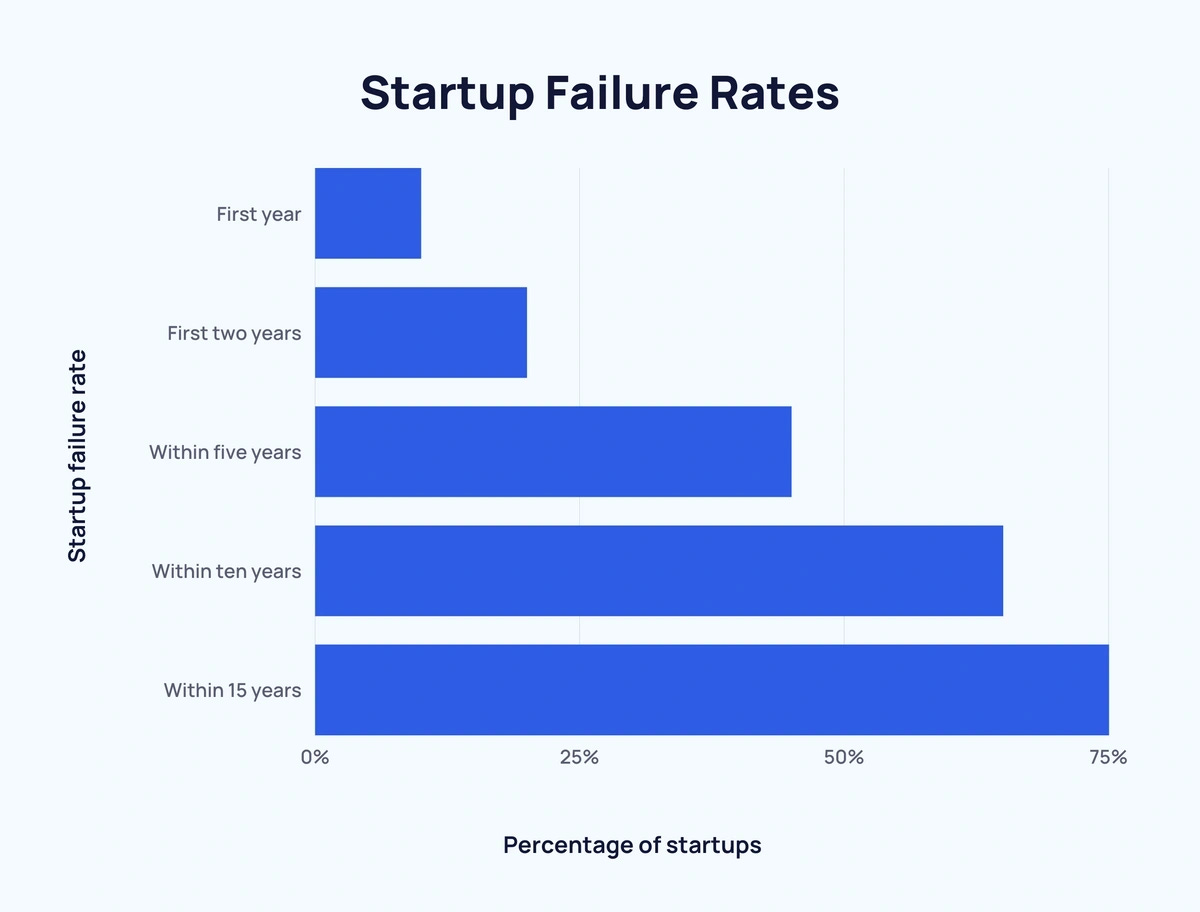

Don’t forget survivorship bias. 90% of startups fail and don’t ever reach the next stage in the lifecycle. This is the inverse power law.

Takeaway 1: Look for companies that have a history or the possibility of reinvesting themselves. This is optionality, which is often difficult to value.

But some concepts govern these stages. Let’s list them now and discuss them in detail later:

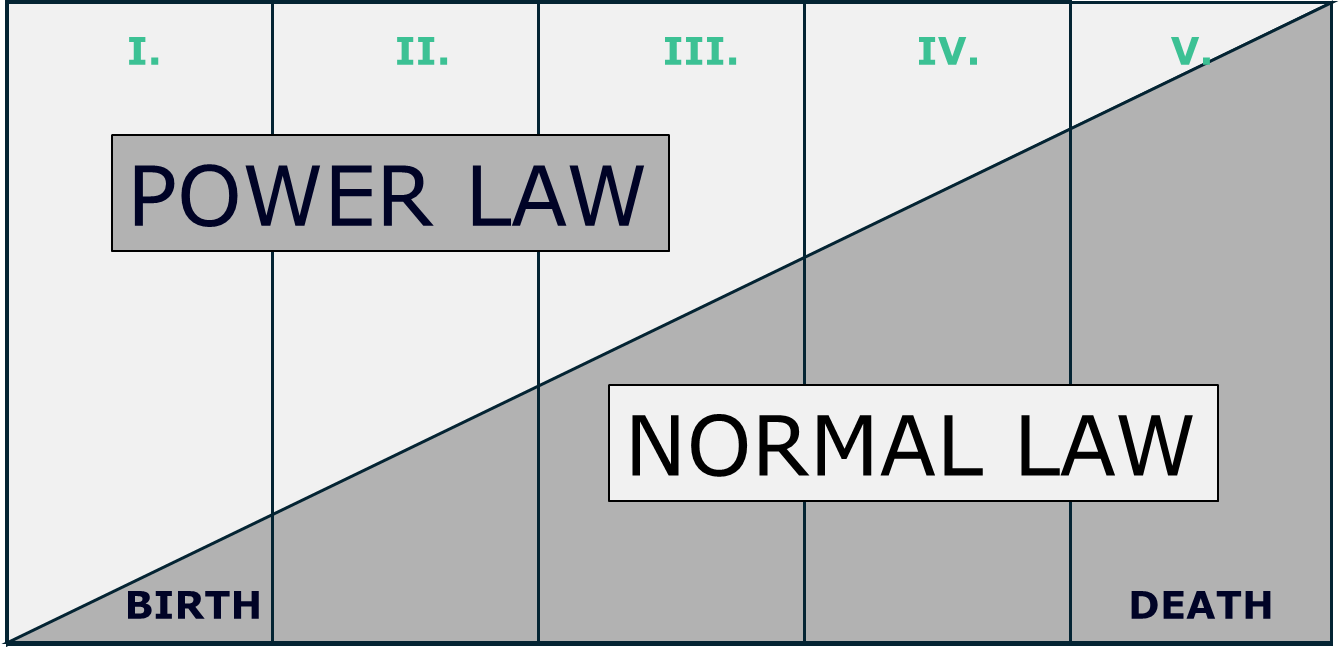

Power laws

Investing is dominated by power laws. A few small winners generate 80% of the return in your portfolio. The younger the companies you invest in, the more you will need this power law to generate a decent return. A venture capitalist specifically hunts for companies that could be the next outliers. This even applies to the entire market. According to Bessembinder, the best 4% performing stocks of the market accounted for all the outperformance. This means 96% of them, over the long term, did not beat the performance of treasury bills.

Takeaway n° 2: Hunting for multibaggers = hunting for a power law outcome

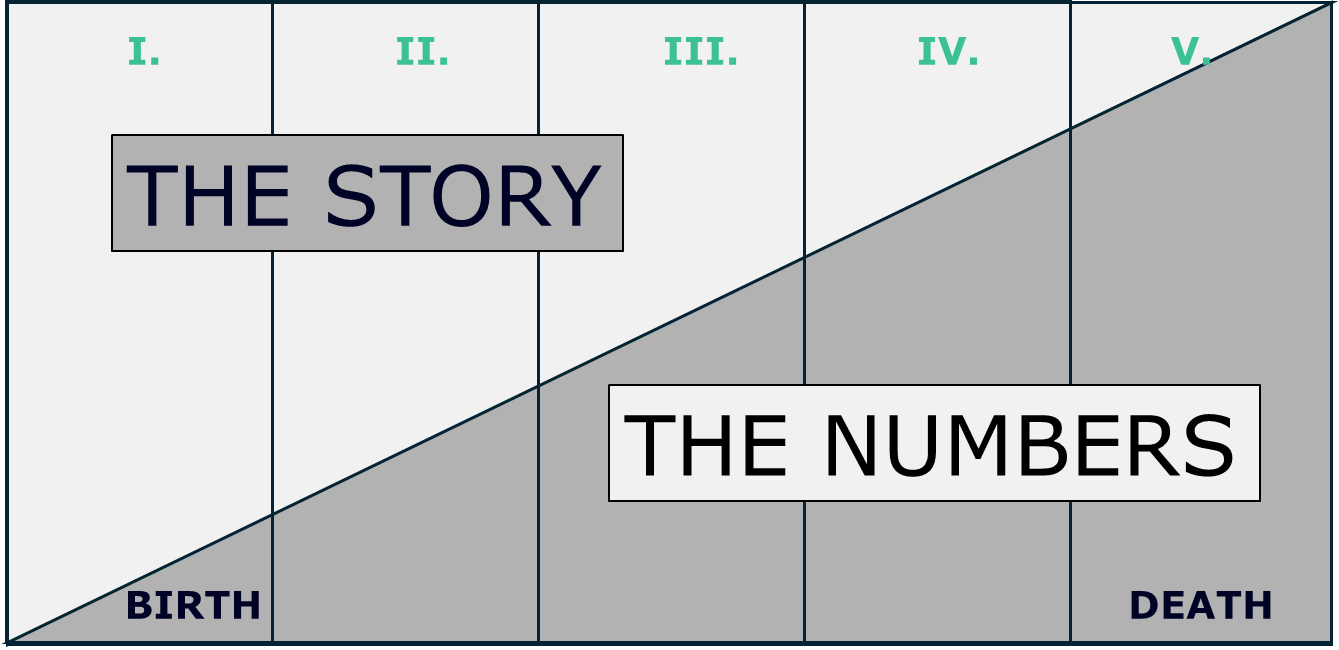

The story

Narrative vs numbers. The only thing a startup has is a story. A bold vision of a new future. A VC has to bet on the story and the founder. This changes over the course of the lifecycle. As a company grows older, it has more history and more numbers behind it. The number gradually becomes more and more important, until the company reaches the decline phase, and numbers are all that matter. (Some investors focus specifically on distressed assets investing; this is reserved for specialists, but they can calculate in detail what the possible undervaluation is.)

Takeaway n° 3: If you're investing in stage 3, high-growth companies with a history in numbers, you still need to bring in the story. Focusing on numbers alone will not be enough.

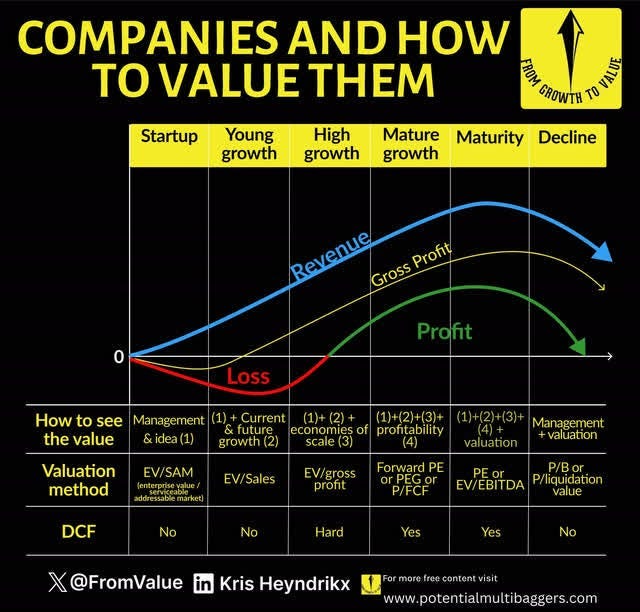

Valuation

You guessed it.

You cannot value a company in startup mode the same way you value a company in its mature phase.

My friend over at Potential Multibaggers made a great chart to visualize this. Let’s take a look:

Let’s go through them:

Stage 1: Startup

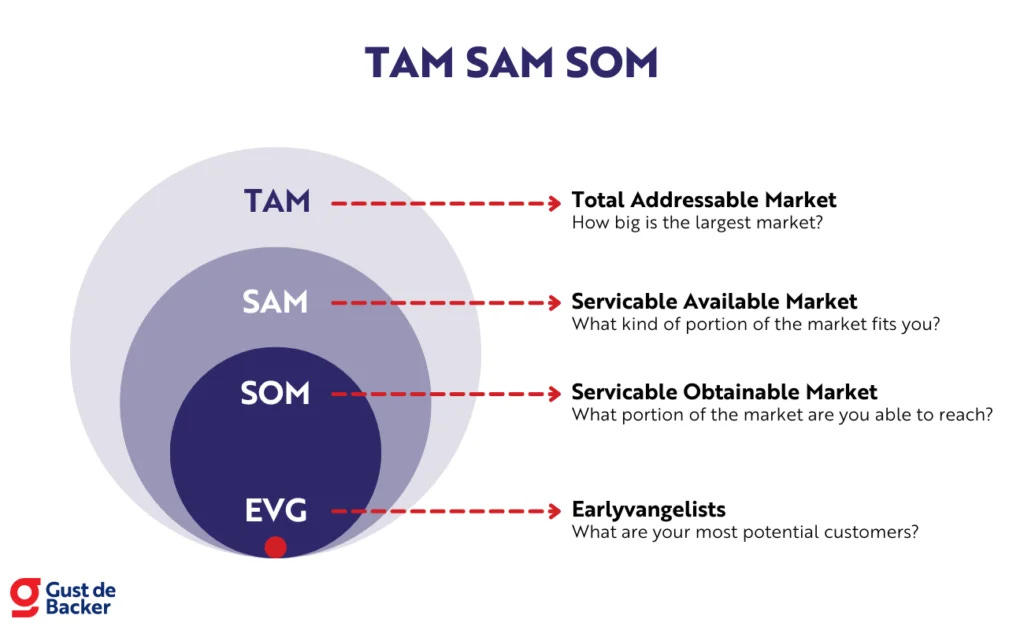

If the startup is pré-revenue, then I hope the company’s pitch deck includes something like this:

TAM or Total Addressable Market: Total market demand for a product or service

SAM or Serviceable Available Market: The portion of the TAM that the company should be able to reach with its current business model

SOM or Serviceable Obtainable Market: The portion of the SAM that the company should be able to reach in the short term

You can then create an EV/SAM multiple.

More often, if the company does have sales already, you’ll see VCs juggle with EV/sales multiples.

A discounted cash flow?

Nah.

Stage 2: (High) Growth

This stage is dominated by high growth rates, where at a certain point, net income growth might be achieved.

Companies in this stage might not focus on the bottom line just yet. They want to continue to capture market share. We have to move up in the income statement, and a good proxy is to use EV/Gross Profits.

You could do a DCF or reverse DCF. But the high growth rates make it difficult.

Stage 3: Mature (Growth)

The companies are still growing faster than the GDP growth rate, but the business models have stabilized. There is a steady net income with probably some operational leverage. You could use a multiple like the P/E or the PEG if you want to include growth. But be mindful that the P/E is a shortcut to valuation.

A reverse DCF is probably best here.

The earlier in the stage, the more uncertainty, the wider the number of scenarios, and the more difficult to value the company.

Stage 4: Stable (Growth)

The companies are now growing along with the economy. Steady growth. Maybe they have a buyback program and are trading at a low P/E, which could be very accretive to shareholder value.

You can use the trailing P/E multiple or do a reverse DCF.

Stage 5: Decline

You’re now in liquidation territory. There could still be value here. If a company is close to bankruptcy, the market might have overreacted and pushed the price below its liquidation value. These are special situations, but can be profitable.

You can use the Net Cash Asset Value, or Sum of the parts, or the liquidation value. Be mindful that calculating this is easy when the company has tangibles on the balance sheet, but difficult for a software company.

DCFs are pretty useless here. Or are they useless all the time? ⬇️

Takeaway n°4: Use the right valuation approach for each stage

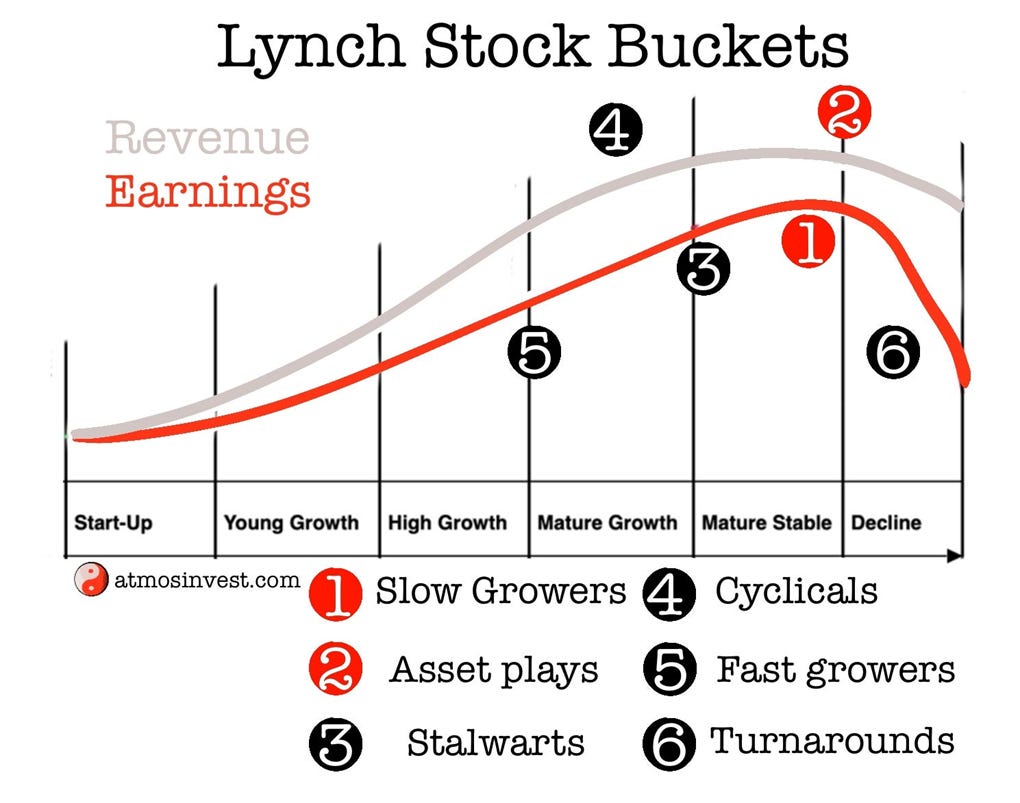

Peter Lynch

Peter Lynch was known for investing in growth companies. But Lynch invested in various types of companies, all according to their stage in the life cycle.

He identified the following types of companies:

The slow growers

Asset plays

The stalwarts

Of cyclicals

The fast growers

De turnarounds

Once you know where the company is in the lifecycle, you need to apply other tools or perspectives.

One of his sayings: You don't use a hammer to tighten a screw

In other words, you need to use the right tools depending on the type of company you are analyzing.

The neat side of his strategy: You always find something interesting to do in the markets. Is growth overvalued? -> Go look at another stage.

Takeaway n°5: Investing over the entire lifecycle increases your skillset. You’ll always have something to do, regardless of the economic cycle.

Conclusion

Here are the 5 takeaways when hunting for 100-baggers through the lens of the company’s lifecycle:

Look for optionality, possibilities where a company can fight its age

The power law is most present in stage 1 and not present in stage 5. Hunting for multibaggers = hunting for power laws

Hunting for 100-baggers means taking into account the story. You cannot get there on numbers alone

Although valuation is an art, you need to apply the right toolbox in the right life cycle stage.

Hunting throughout the different stages increases your skillset, makes you flexible

May the markets be with you, always!

Kevin

Please rate this article:

Check out this multi bagger idea - quick read

I’m catching up a little late, but this was a great breakdown. Love the point about using different tools for each stage—too many people try to force every company into the same model, and then wonder why their results are so hit or miss.

Also really appreciate the reminder that you don’t have to be dogmatic about style. Sometimes the best opportunities are in spots other investors ignore because it doesn’t fit a strict “growth” or “value” label.

The lifecycle lens is useful for staying flexible and not getting stuck when one part of the market cools off. Good stuff.