GPT5: Will it supercharge your stock analysis?

Applied to The Trade Desk(TTD)

"You know the business, and I know the chemistry. I'm thinking... maybe you and I could partner up." — Walter White to Jesse Pinkman

What GPT5 meant when he quoted this from Breaking Bad is that I will play the role of Walter White, knowing how to analyze stocks. GPT-5 will play Jesse, knowing neural network-based predictions and having advanced analysis capabilities.

So today, GPT5 will be my Jesse, and we’ll try to cook up something magical. We’ll compare our batch to the work I did with his brother Grok-3 a couple of weeks ago.

And we’ll end this article with a multibagger mega-prompt I built.

A Mega-prompt? Yes, a 3-page-long stock investing prompt, which provides a high-quality output result.

Here’s the 3-part cooking recipe we’ll follow today:

GPT-5: What kind of beast is it?

5 prompts applied to The Trade Desk(TTD)

Conclusion: Is GPT-5 Worth it? And what to do with TTD?

Bonus: A Multi-Bagger Mega-Prompt

GPT-5 Overview

Before diving into the prompts, let’s first compare some of the models to GPT-5

Here’s the new screen you’ll see when you open up ChatGPT.

One of the first things we notice is the model selector. We only have 2 options:

GPT-5

GPT-5 Thinking

You can select the older models in the Pro Subscription, but just like Grok-4, ChatGPT is taking the approach of a Unified User Experience. -> Based on your query, it will use the best model for that query.

This is a great advancement because at a certain point, there were A LOT of models to choose from.

However, after testing it for several hours, you can summarize this into:

You want a fast answer: GPT-5

You want a deeper but slower answer: GPT-5 Think

That’s it.

We have no idea if it is “choosing the right model in the background”.

Here’s a quick comparison of the differences between GPT4 and 5:

There are some bold statements in there (coming from OpenAI):

PhD-level reasoning

Your Team of experts

Superior Agentic Workflows

Sounds promising.

But what about the new model’s performance?

Benchmarks

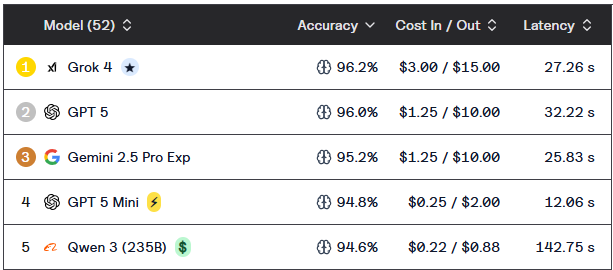

The first benchmarks are available on GPT-5 ⬇️

AIME benchmark

In one of the Math benchmarks, GPT-5 takes back the crown from Grok-4

Gradually getting closer to that 100% mark. Let’s take a look at another one.

MATH Benchmark

Grok-4 still reigns supreme, but only barely.

Let’s look at a final one of these benchmarks: coding

LiveCodeBench

Where GPT5 mini is the winner (which we cannot manually pick with our subscription)

This is great, but our purpose is to analyze stocks.

Sadly, at the time of this writing, no updated benchmark on Finance includes GPT-5. I’ll post it in the chat once they do.

Based on these benchmarks, GPT-5 seems to take the lead as compared to Grok-4. Let’s see how good GPT-5 is when feeding it some quality prompts.

We’ll apply it to a company called The Trade Desk (Ticker: TTD), down 30% after its latest earnings report.

A high-quality company? Let’s find out.

The Trade Desk - investing prompts analysis

We’ll use the same prompts as in our previous article.

First impression. GPT5 is super fast. It gives me an immediate answer to my prompt. This already gives me a first conclusion. You can’t compare GPT-5 to Grok-4. The right comparison is:

Grok-3 vs GPT-5 (both fast models)

Grok-4 vs. GPT-5 Thinking (both slower models)

Because for the same prompts, Grok-4 will start searching and thinking, while GPT-5 almost immediately answers.

Let’s go through the analysis.

Prompt 1: Understanding the business model

Prompt

The company we are researching today is called The Trade Desk, which is publicly traded on the NASDAQ Exchange with the ticker TTD. Can you go through the publicly available filings and other sources and break down the business model for me? How does this company make money, and what does it need to do to generate its business? Is it a capital-intensive business? Please explain it to me like I’m an 8-year-old. Provide an example to illustrate the business model.Output

What The Trade Desk (TTD) is

TTD runs a demand-side platform (DSP). Think of it like a super-smart shopping cart for ads on the open internet (websites, streaming TV, audio, mobile apps, outdoor screens). Advertisers and agencies log in, set goals and budgets, and the platform buys the best ad slots in real time. thetradedesk.com

How TTD makes money (in plain English)

They charge a platform fee that’s usually a percentage of what clients spend through TTD. That’s it. They don’t buy ads and mark them up; they earn a cut (often called a “take rate”) of the ad spend that flows across their platform. In 2024, advertisers ran ~$12.0B of spend through TTD, and TTD booked $2.45B of revenue—illustrating the “percentage-of-spend” model. SEC

Revenue is reported net of what flows to publishers and data suppliers (so revenue is much smaller than “gross spend,” by design). SEC

What TTD must do to generate business?

Have lots of places to buy ads: deep integrations with publishers, supply platforms, and new channels like connected TV (CTV). SEC

Offer great targeting & measurement: identity tools like Unified ID 2.0 (UID2) help advertisers find the right audiences and measure results as the web gets more privacy-centric. thetradedesk.com+1

Keep improving the software (bidding, optimization, APIs) so agencies keep routing spend to TTD instead of rivals. SEC

Is it capital-intensive?

Not really. It’s a software platform, not a factory. The big costs are cloud hosting, data, and people (recorded in operating expenses). Capital expenditures (servers, offices, capitalized software) were about $98M in 2024—roughly low-single-digits as a share of revenue—so this is asset-light. SEC

Kid-level analogy (you asked for 8-year-old mode)

Imagine a giant vending machine of ad spots around the internet. Brands put money in, tell the machine “find soccer moms watching streaming TV” or “people who like toy cars,” and the machine instantly bids for the right spots as shows and webpages load.

TTD owns the machine’s brain. Every time money goes through the machine, TTD keeps a small slice for running the brain.

One concrete example

A toy company wants parents to see a 15-second video ad on streaming TV during kids’ shows this weekend. In TTD:

The marketer sets a €1M budget and goals (reach parents with toddlers; frequency ≤ 3).

TTD’s system connects to lots of TV apps/sites and bids in real-time for each eligible ad slot.

It uses identity and measurement tools (e.g., UID2 plus retail/measurement partners) to aim at the right households and prove the ads worked.

Suppose €1M runs through TTD; publishers get most of it, data vendors get a bit, and TTD takes a platform fee (its revenue). SECthetradedesk.com

Quick facts from filings (to ground this)

Revenue model: platform fee as a % of client spend; clients control buying; transparent “clear box.” SEC

Scale: $12.0B gross spend and $2.45B revenue in 2024. SEC

Costs/capex: hosting & data in operating expenses; $98M capex in 2024 (asset-light). SEC

If you want, next we can map the competitive moat (CTV strength, agency relationships, UID2 adoption), the key risks (identity changes, competition, macro ad spend), and valuation versus peers—and build a simple model.

Discussion

I believe anyone can understand what The Trade Desk does with this prompt.

The one part I find especially strong is what GPT5 asks at the very end:

What GPT-5 proposes is not just some shallow or random follow-up. This is specific. And spot on, exactly one of the questions you want when doing your research.

I tested Grok-4 with the same prompt, and the output is quite different. Grok does not provide this quality of follow-up.

However, Grok goes a lot further in (Explain it to me like I’m an 8-year-old). GPT-5 does provide a single paragraph on the 8-year-old.

This is, of course, subjective, but Grok nailed the 8-year-old output result. Here’s a sample he gave that makes you immediately understand the business model of The Trade Desk:

Pretend you're a kid with a lemonade stand, and you want to tell everyone in town about your yummy lemonade. You go to The Trade Desk's robot and say, "Show my ad to thirsty kids playing games on their tablets this afternoon." The robot scans a bunch of ad spots (like empty signs on game apps) that are up for auction. It bids super quick—maybe wins a spot for $10 (that's what you pay the app owner). But The Trade Desk takes its fee, say $2, so you pay $12 total. Boom! Your ad pops up, kids see it and come buy lemonade, and The Trade Desk gets paid for being the helper. If lots of kids like you use the robot every day, The Trade Desk makes a bunch of those little fees add up to big money

Conclusion: TTD is a low CAPEX business. It charges a small fee from a large money pool (which I like). It has a decent take rate of about 20%.

But we need more information.

Prompt 2: Are there signs of counter-positioning?

Prompt

Does their business model show signs of counter-positioning towards established businesses? How many other companies are there out there that are similar to The Trade Desk? If there are only a few, why is that? Are there any particular barriers to entry? Why does the establishment not replicate what this company is doing?Output

1. Quick refresher — what “counter-positioning” means

This is a term from Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers:

A newcomer adopts a business model the incumbents can’t copy without hurting their own existing business.

Classic examples: Netflix streaming vs. Blockbuster’s late-fee model, or Tesla direct-to-consumer vs. dealer networks.

2. Does TTD’s model fit counter-positioning?

Yes — partially.

TTD operates on the open internet with a transparent, buy-side-aligned model:

Revenue is a fixed take rate (not media arbitrage), so advertisers know exactly what TTD earns.

Clients own their data and decisioning, and TTD plugs into many supply sources — no “walled garden” conflict.

Why incumbents struggle to copy it:

Large incumbents like Google DV360, Amazon DSP, and Meta Ads make most of their money from selling their own inventory at high margins.

If they offered a truly neutral, transparent DSP across all inventory (including rivals’), it could:

Cannibalize their high-margin owned-media sales.

Expose performance data from walled gardens to third parties, undermining control.

Reduce lock-in advantages.

That’s the counter-positioning tension: replicating TTD’s model means undermining the very moat that keeps incumbents strong.

3. How many companies are like The Trade Desk?

There are a handful of independent, scaled DSPs, but far fewer than a decade ago:

Independent DSPs: The Trade Desk, MediaMath (in distress), Zeta Global (smaller share, also a CRM/marketing cloud hybrid).

Agency-housed DSPs: Xandr (Microsoft, more supply-side now), Amobee (acquired, repositioned).

Platform-owned DSPs: Google DV360, Amazon DSP, Adobe Advertising Cloud, Yahoo DSP — but these are not fully independent.

Today, The Trade desk is the only large, profitable, pure-play, independent DSP of global scale.

4. Why so few?

Three main reasons:

Scale economies in data & access

Real-time bidding requires massive infrastructure, global supply integrations, and machine-learning optimization at scale. This is expensive to build and sustain.Network effects with agencies & data partners

Agencies consolidate spend with a few trusted DSPs to get volume discounts, better integrations, and unified reporting.Trust & neutrality

Advertisers want their data protected and not used to benefit a media seller. TTD built a brand around being a “clear box” platform — something hard for vertically integrated ad sellers to credibly claim.

5. Barriers to entry

Technical moat: handling millions of auctions per second with low latency and advanced AI bidding is non-trivial.

Ecosystem integration: deals with supply partners, measurement firms, identity systems, and agencies take years to develop.

Reputation & relationships: Once a DSP is embedded in an agency’s workflow and reporting, switching is costly and risky for the buyer.

Data scale: better models come from more bidding and impression data; small entrants can’t match the training set.

6. Why doesn’t the establishment just copy it?

Incentive conflict: To be truly neutral, they’d have to help advertisers spend outside their own platforms — which reduces the share of wallet they capture.

Organizational inertia: Big platforms optimize around their owned-media margins; building a neutral, low-take-rate model is a cultural and P&L shift.

Loss of control: Opening up measurement and targeting data weakens their lock-in advantages.

Bottom line:

TTD’s model does have counter-positioning power — it’s not that Google, Meta, or Amazon can’t build something similar, it’s that doing so at TTD’s transparency and neutrality would undermine their existing business models. Combine that with tech, data, and relationship moats, and you get a field where there’s really only one large, profitable independent DSP left.

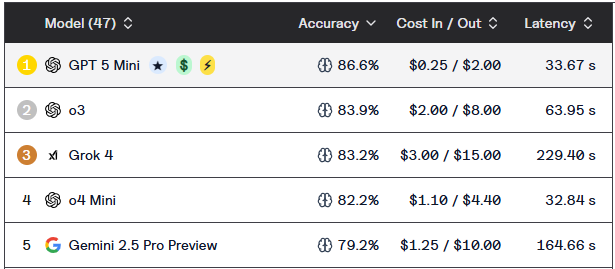

If you want, I can map out TTD’s competitive moat diagram showing exactly how counter-positioning interacts with scale economies and network effects so you can visualize why it’s been so hard to displace them. That’s often a useful prelude to assessing investment durability.

So I respond, hell yeah, let’s do this!

The result was this:

Mweh. That’s not the greatest of diagrams. So it’s not up to par yet to visualize logic.

Because it’s so fast. Despite the high-quality response, there are no sources. It did not search the web for additional information. This may be because we’re using the normal mode as opposed to the Think mode.

Discussion

Again, a solid analysis. I do believe TTD is counter-positioned. It talks about barriers to entry, only a few competitors, and that Amazon will have to cannibalize its own business if its wants to compete one-on-one with TTD.

Let’s keep going ⬇️

Prompt 3: Test Scale Economies Shared

Prompt

A business like Costco uses a model that is called Scale-Economies-Shared. This was popularized by the investor Nick Sleep. It means when a company grows and generates more cash, it uses parts of that cash to distribute back to the customers in some way. Costco uses this to guarantee the lowest prices for its customers as it scales. Is The Trade Desk doing something similar? Is there proof of a scale economies shared business model?Output

Got it — you’re asking if The Trade Desk is essentially a “Nick Sleep-style” scale-economies-shared business:

As the company scales and becomes more efficient, does it pass a chunk of those benefits back to customers, strengthening loyalty and moat?

1. The essence of Costco’s model

As Costco grows, its purchasing power and operating efficiency improve.

Instead of keeping all the savings as profit, it lowers prices (or improves value) for members, reinforcing the “cheapest place to shop” perception.

The flywheel: more customers → more scale → more savings → lower prices → more customers.

2. Applying the lens to The Trade Desk

TTD’s “customers” are advertisers and agencies, and its “price” is the platform fee (take rate). It doesn’t sell goods, but it sells media-buying efficiency.

Evidence of scale-economies-shared in TTD’s model:

a) Transparent, fixed take rate

TTD publicly emphasizes a “clear box” model — advertisers see exactly what they pay TTD, usually a small percentage of media spend.

As volume grows, TTD invests heavily in:

Better targeting (e.g., Unified ID 2.0, retail data integrations)

Better measurement (conversion tracking, cross-device attribution)

Better supply access (exclusive or early access to premium CTV inventory)

Instead of jacking up the take rate to capture more of the value, TTD keeps it stable and uses scale to make the platform more effective per dollar spent.

b) Heavy reinvestment into R&D and partnerships

R&D spend in 2024 was over $500M+ (around 20%+ of revenue) — high for a software platform at this maturity.

The benefits (higher ROI per ad dollar) accrue to customers directly. If TTD’s algorithms get 10% more efficient at finding the right impression, that’s value the advertiser captures.

c) Building free, open infrastructure for the industry

UID2 is essentially given away — TTD leads and supports it, but makes it open-source. This helps the whole open internet compete with walled gardens, indirectly improving value for clients.

3. Is there proof of scale-economies-shared?

We can’t “see” this the same way you can see Costco lowering prices, but the pattern shows up in the spread between TTD’s take rate and its margin expansion potential:

Take rate is stable despite rising volume — no evidence of creeping “ad tax.”

Gross margins stay high (~78%) and operating leverage is increasing, but instead of maximizing operating margin now, they keep plowing cash into product and integrations.

Platform capabilities for the client improve year after year without proportional price increases.

That’s arguably the ad-tech equivalent of Costco’s “we get cheaper, you get cheaper goods” — here it’s “we get more efficient, your ads get more effective per dollar.”

4. The flywheel (TTD-style)

More advertisers → more spend → more bidding data & better models.

Better models → better campaign performance for clients.

Better performance → advertisers allocate more budget to TTD.

Scale lowers per-unit tech & data costs, allowing more investment in performance features without raising take rates.

Loop back to step 1.

5. Key difference from Costco

Costco’s benefit to customers is direct price reduction.

TTD’s benefit is better ad outcomes for the same price (stable fee, improved tech, better supply, more transparency).

The “return” is less visible to the client’s accounting team, but in media ROI terms, it’s real.

Conclusion:

Yes — The Trade Desk exhibits a software-age version of scale-economies-shared.

Instead of lowering a shelf price, they:

Hold take rates steady

Use scale to reinvest in features, integrations, and data that improve clients’ ROI per dollar

Provide free/open infrastructure (UID2) to strengthen the ecosystem their clients depend on

It’s subtler than Costco’s model, but the competitive logic is the same: give customers more value as you get bigger, so they stick and spend more.

If you want, I can chart TTD’s take rate stability vs. revenue growth alongside R&D spend as % of revenue over the last 5–7 years — that’s the clearest quantitative evidence that they’re not milking scale for short-term margin, but reinvesting it into client value. That’s where this theory turns into numbers.

Discussion

It makes a great comparison between Costco and TTD and concludes that TTD has Scale Economies and Shared traits, but they are different than Costco.

Costco will use its scale to keep prices the lowest.

The Trade Desk will use its scale and keep its take rate stable, while increasing the value to its customers.

Again, I want to emphasize the last paragraph of its output.

Now, the fact that it proposes a next step is great.

But the quality of those next steps is what surprises me. It’s talking back like an actual analyst.

However,

I’ll just share one final comment GPT-5 Think made that I think is awesome:

Anyone can understand this. In other words, it says TTD keeps charging at the same rate, but makes the product/service better and better.

So is it leaving profits on the table then and pushing them into the future?

Now again, it proposes to chart the take rate stability vs R&D spend.

Let’s oblige it ⬇️

Ok, I began to think the new GPT had easy access to financial data. So that’s a first limit we run into.

Prompt 4: Market potential

Prompt

Based on the current revenue size of the company, how big is the potential future market for this company? Give us a bear, base, and bull case view of what the future market could be for this company. If possible, translate this into a possible revenue number for each case, 5 years from now.Output(partial)

Discussion

Full year 2024 revenue was 2.4B in revenue. So even the bear case projects growth. But as with Grok, we need to be skeptical of these models.

Let’s compare this result with GPT-5 thinking mode, as it will use more brain power

Now the model is a lot more conservative.

What is positive is the fact that for each case, it mentions the story. Since this is my first analysis of TTD, what can I make of this?

The market it is competing in is set to grow. I would need to dig deeper to get a better idea of how TTD could evolve its market share in a growing market. But based on the counter-positioning statement, in the open market, since it is one of the dominant players, it should be able to gain more share.

Let’s go to the final prompt

Prompt 5: Red Flag Analysis

Prompt

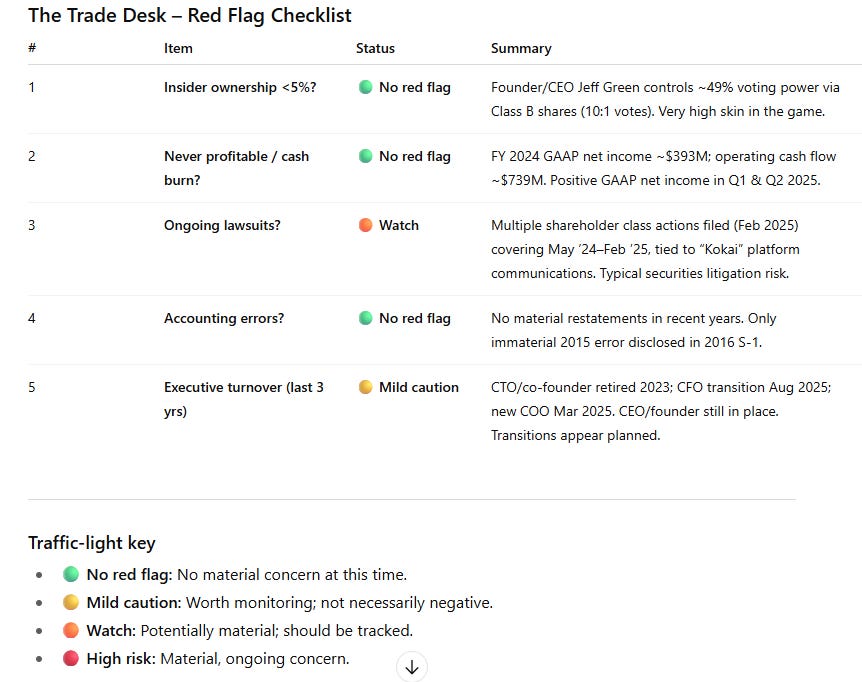

I would like to identify any red flags surrounding this company that would prevent me from considering it as an investment. Here are 5 red flags I want you to research and identify. 1. Is there low insider ownership (<5%), which would imply low skin in the game? 2. The company has never been profitable in its history and is still burning cash. 3. Are there lawsuits ongoing concerning this company? 4. Have accounting errors surfaced in the past? 5. Has there been a lot of turnover in the executive team of this company over the last 3 years?Now the results were similar to what we did with Grok-3, but the way the output was presented (in red light format) is way better. It also proposed the “watch category, to say you need to keep tracking this closely.

And then it said this

And then I remembered, this version should be able to do more than just provide me with a sheet.

So I asked it to generate me a PDF I could download.

Just like with the chart, that information is there, but it didn’t look good.

Conclusion

Based on my first day with GPT5, I can say that:

Especially the Think mode delivers some of the highest quality feedback I have seen

The proposal given at the end of a prompt output is on point and highly relevant

It cannot generate diagrams or charts yet. Creating a beautiful PDF is a struggle

Compared to Grok? I’ll need to write a head-to-head between these 2. I believe both are powerful at this point.

What to do with the Trade Desk?

Now, let us really put it to the test. The Trade Desk was down 30% on yesterday’s earnings reports.

Let’s say I’m a shareholder. Let’s ask GPT-5 what we should do now. Here’s the prompt I’ve added into GPT-5 Think.

I am a shareholder in The Trade Desk. After yesterday's earnings report, the price has fallen 30% in a single day. Can you analyze the latest earnings report and tell me what action I should take now? Shoud I Trim, Sell, Hold, Buy or Add?And here is the output

My call (based on what we know today)

Base recommendation: HOLD, with a lean-to-ADD in small tranches if your horizon is 3+ years.

Why not sell into this? The drop looks driven by slower near-term growth + leadership optics, not a broken business model. There’s no evidence of a structural share-loss event in adtech; it’s guidance and execution nerves (and yes, the CFO news). If you’re a long-term owner of TTD’s independent DSP thesis (CTV, retail media, open internet), I’d be patient and consider nibbling—but stage entries over a couple weeks rather than catching a falling knife all at once. If you can’t stomach further volatility or your thesis hinges on 20%+ growth every quarter, trim risk.

What (specifically) spooked investors

Guide: Management telegraphed ~14% next-quarter growth—slower than investors wanted for a high-multiple name. Multiple compressions follow guidance cuts, especially after big S&P-500 inflows in July. Barron'sthetradedesk.com

CFO transition: Sudden CFO changes right after a guide-down are read as risk, even if a capable replacement is lined up. Barron's

Recency bias: Recall the Feb 2025 selloff after execution missteps (product rollout/sales reorg). Yesterday’s guide stirs fears that “one-offs” aren’t fully behind them. marketingbrew.com

What to watch before adding more

Transcript/10-Q details: Any change to customer retention (>95%), CTV momentum, or take rate (~20%) would be a red flag. (Those have been stable historically.)

Color on the slowdown: Is it macro budget caution, campaign timing, or internal execution? If it’s timing/execution, reversals happen; if it’s demand-side weakness in CTV/open web, that’s heavier.

CFO handoff plan: How responsibilities are split, and whether there’s reaffirmed full-year targets post-call.

Guide path: Do they imply a reacceleration into Q4/’26, or is mid-teens the new normal?

Action framework (so you’re not guessing)

If you’re long-horizon, thesis-driven: Hold your core. Add 1/3–1/2 position now, another slug after the call transcript/analyst day clarity, and a final slug if the stock stabilizes above post-panic lows.

If you’re valuation-sensitive/low-vol tolerance: Trim to your comfort size and wait for a clean quarter; you can always pay a little more for re-acceleration + execution proof.

If your original thesis required 20%+ growth steadily, The guide to ~14% means your thesis changed—trim/sell makes sense.

Why I’m not saying “sell” outright

Nothing in last night’s reporting suggests the independent, buy-side model is broken; this is about pace and leadership optics.

Even coverage framing the plunge points to decelerating guidance and CFO change as the drivers—not competitive displacement. Barron'sInvestors

If you want, I’ll send you a 1-pager with: valuation vs. 3-yr averages, the exact wording on guidance from the press release/call once the transcript posts, and a trigger list (what would make me flip to Sell vs Add).

You can see that GPT-5 is prudent. It’s a very balanced view, and it probably reflects the articles that have been written since the earnings release.

I know there’s someone on Reddit trading using ChatGPT who has beaten the market (only over a couple of weeks), but this is not how you should use ChatGPT. (yet anyway)

A Multi-Bagger Mega Prompt

I’ve been reading into the most recent reports on advanced prompt engineering to see if I can come up with a high-quality prompt for stock analysis.

Honestly, the prompts you’ve seen up until now in this article pale in comparison to this one.

It took me a while, and I was skeptical about inserting a prompt that is several pages long into Grok or ChatGPT.

I was blown away by the results it gave me.

I’ll explain how to use it. It’s based on Hamilton’s 7 Powers framework, which is an excellent framework to analyze a company for its multibagger potential.

Here’s the full prompt ⬇️